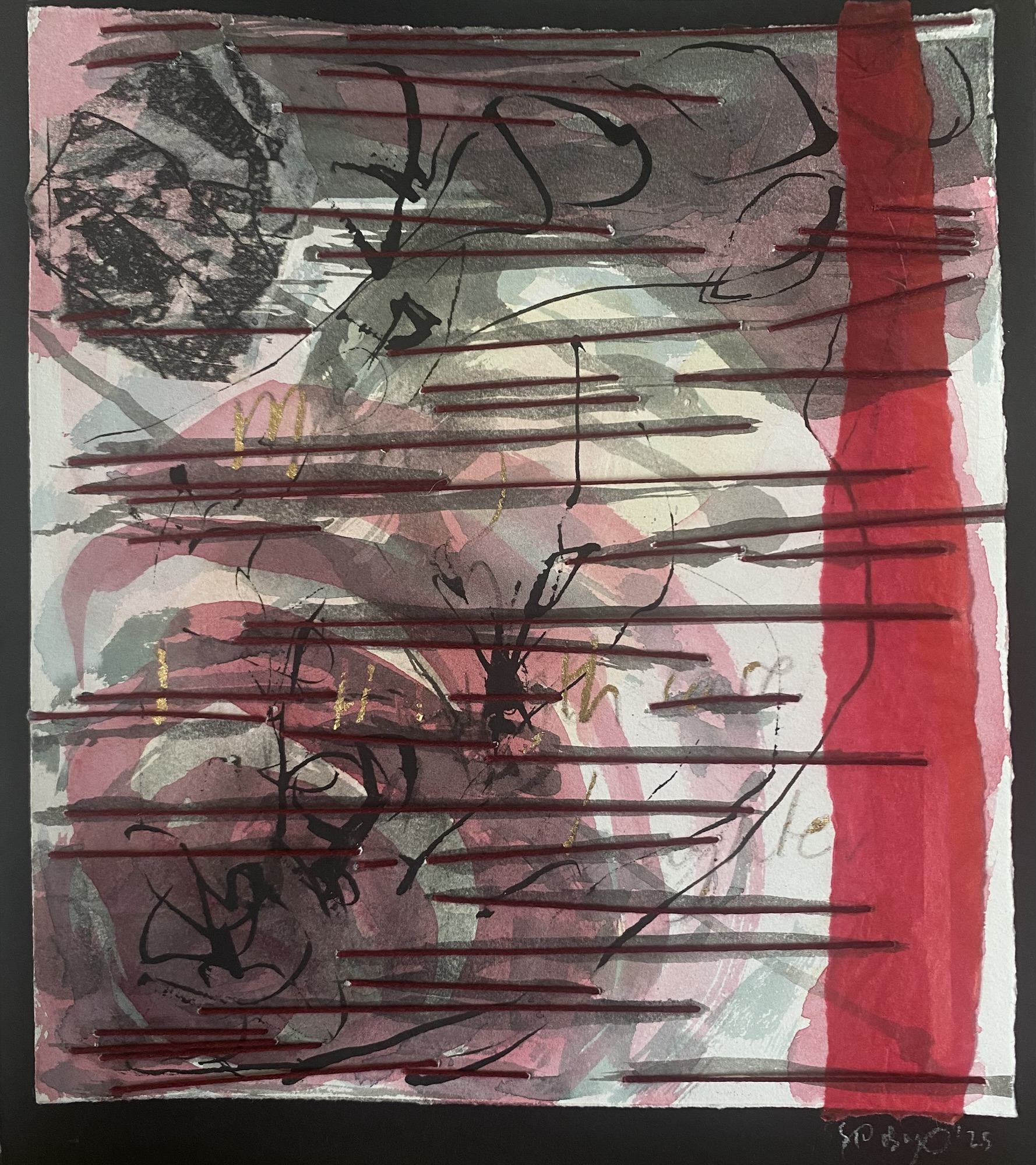

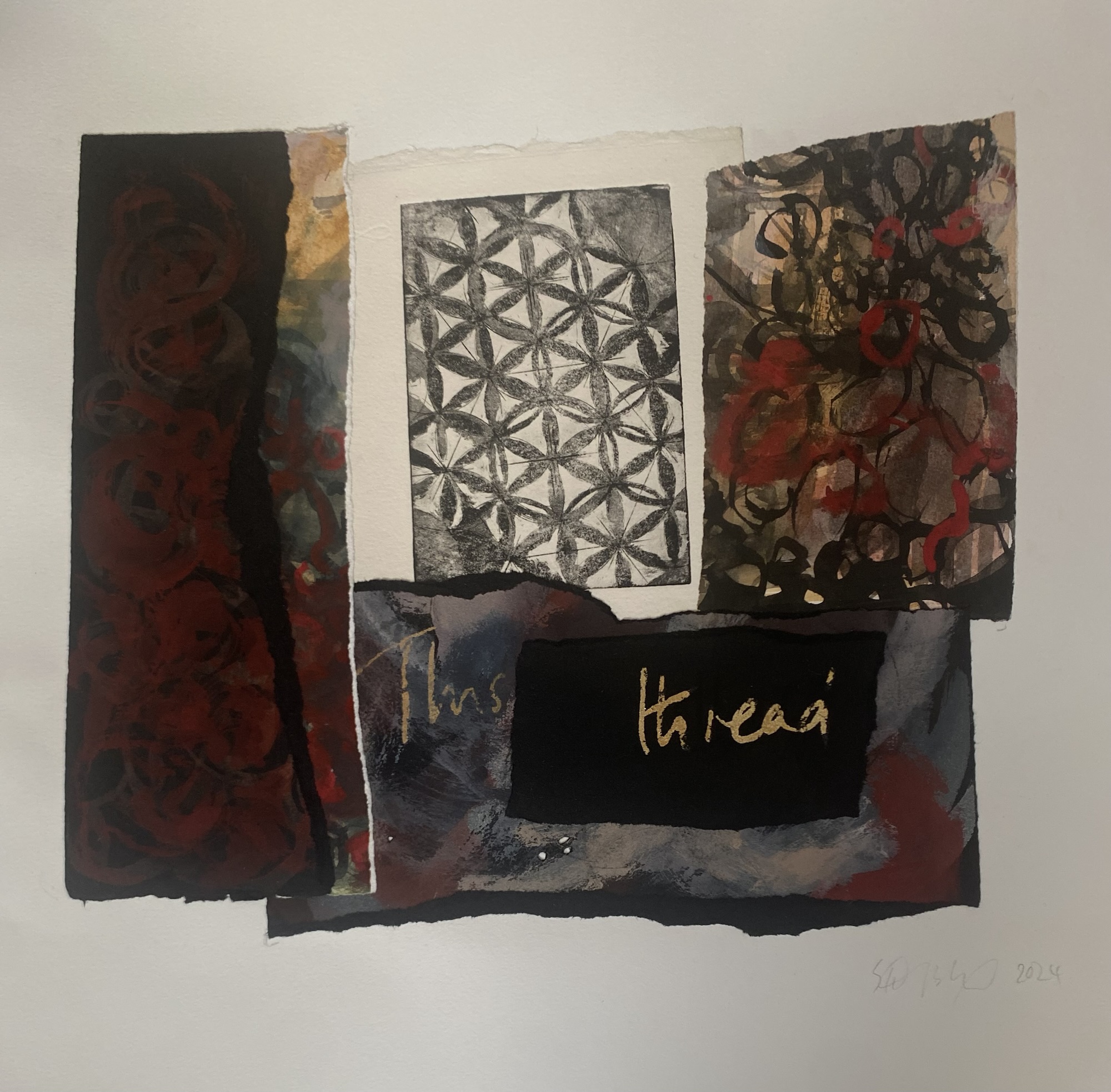

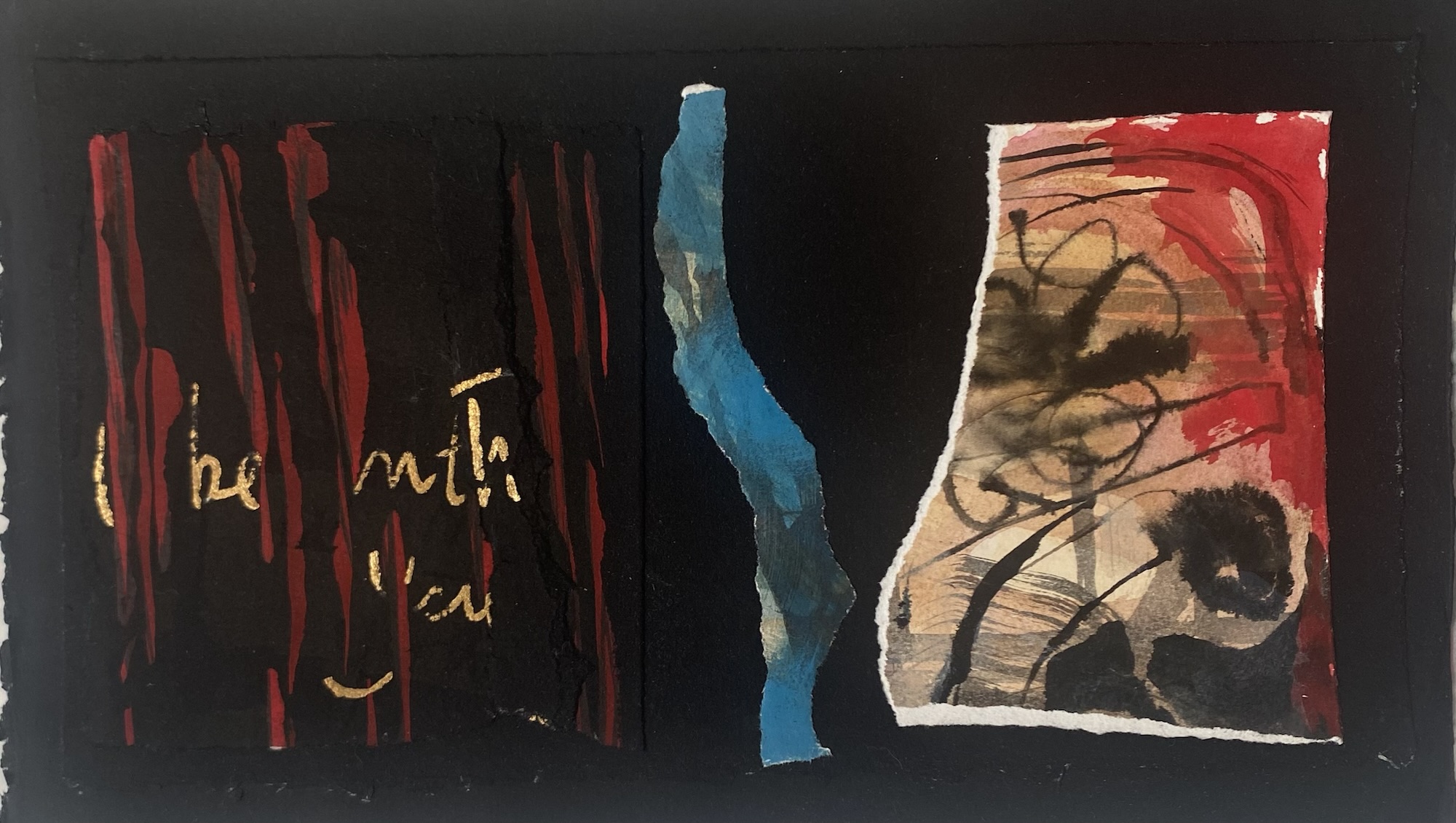

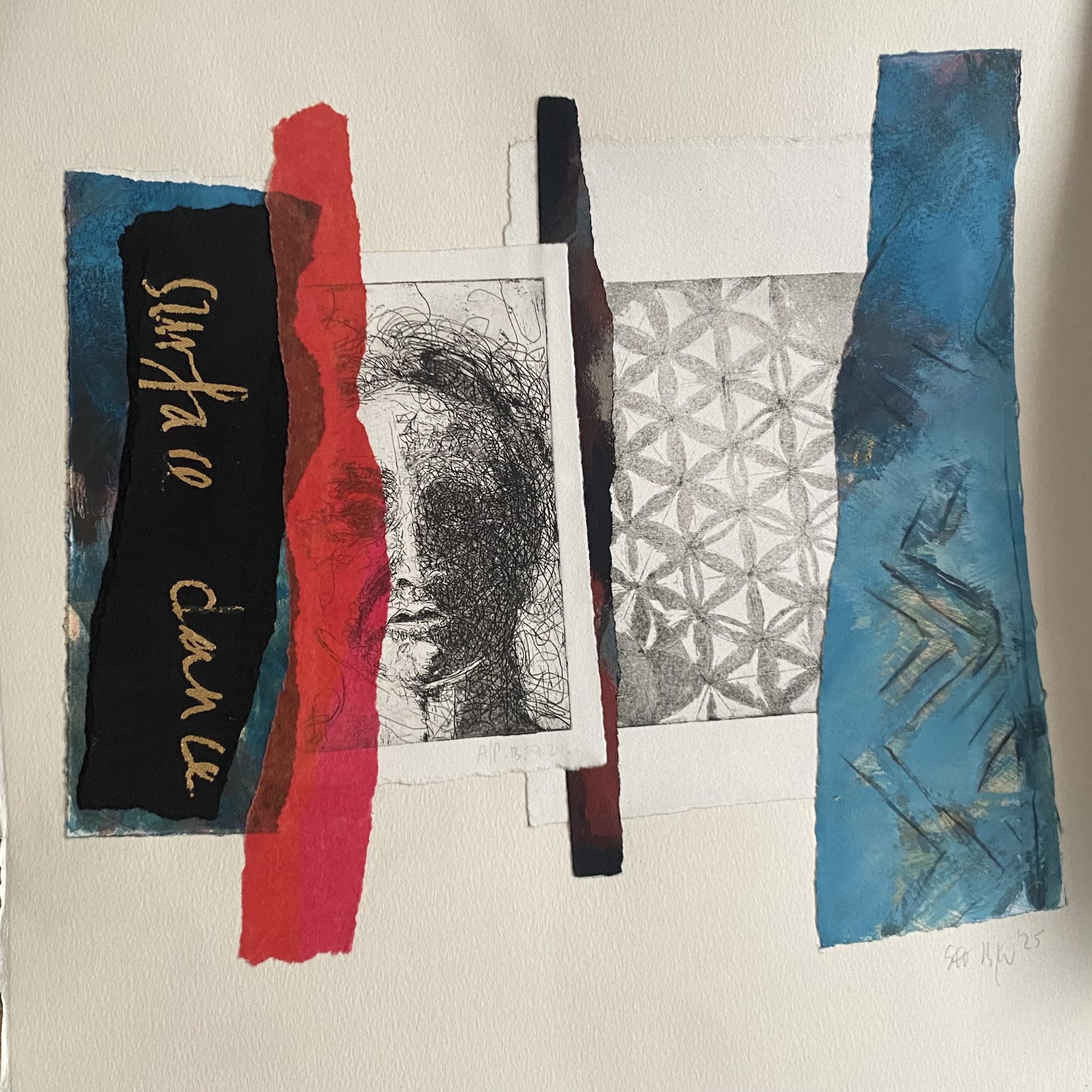

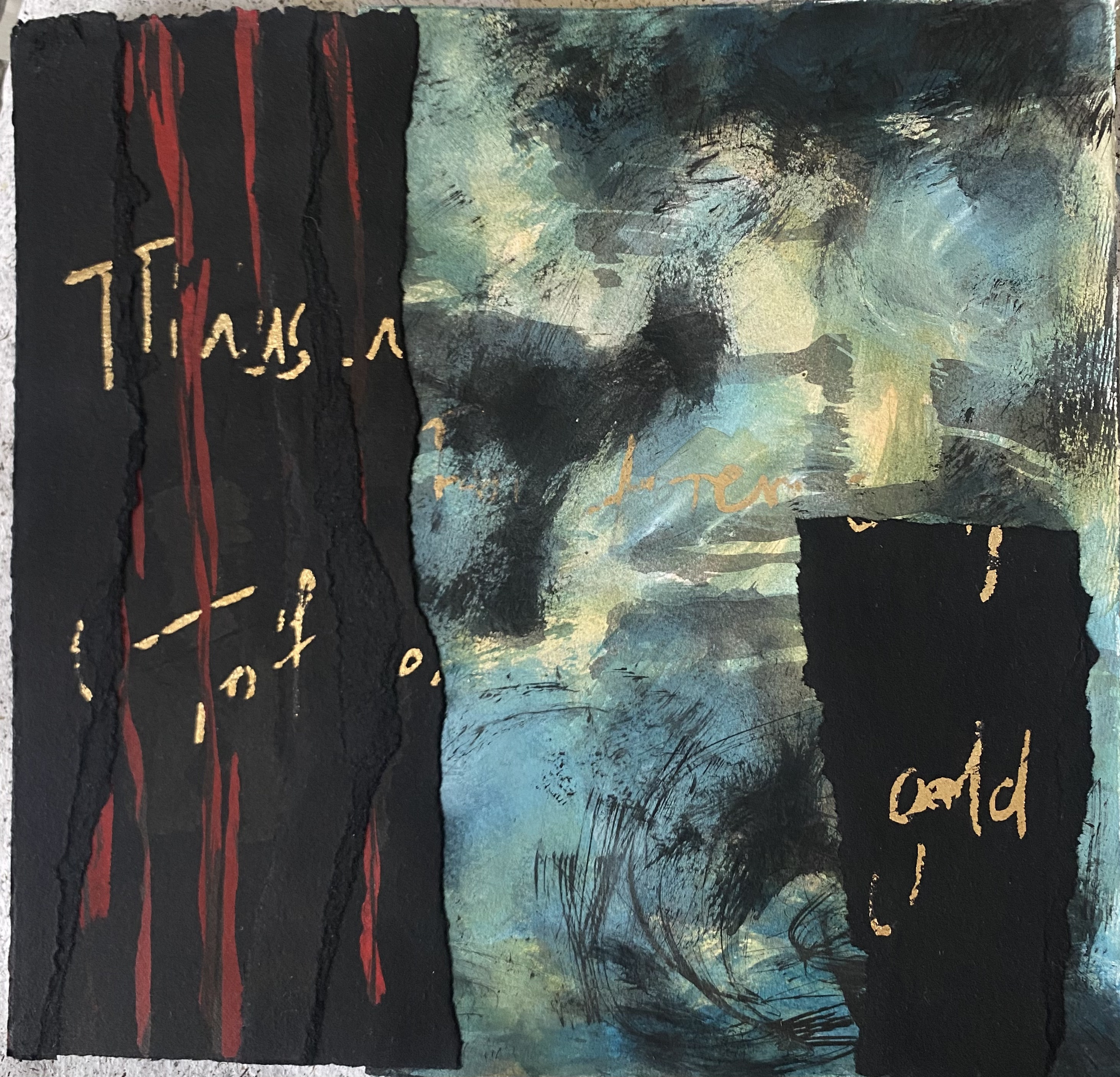

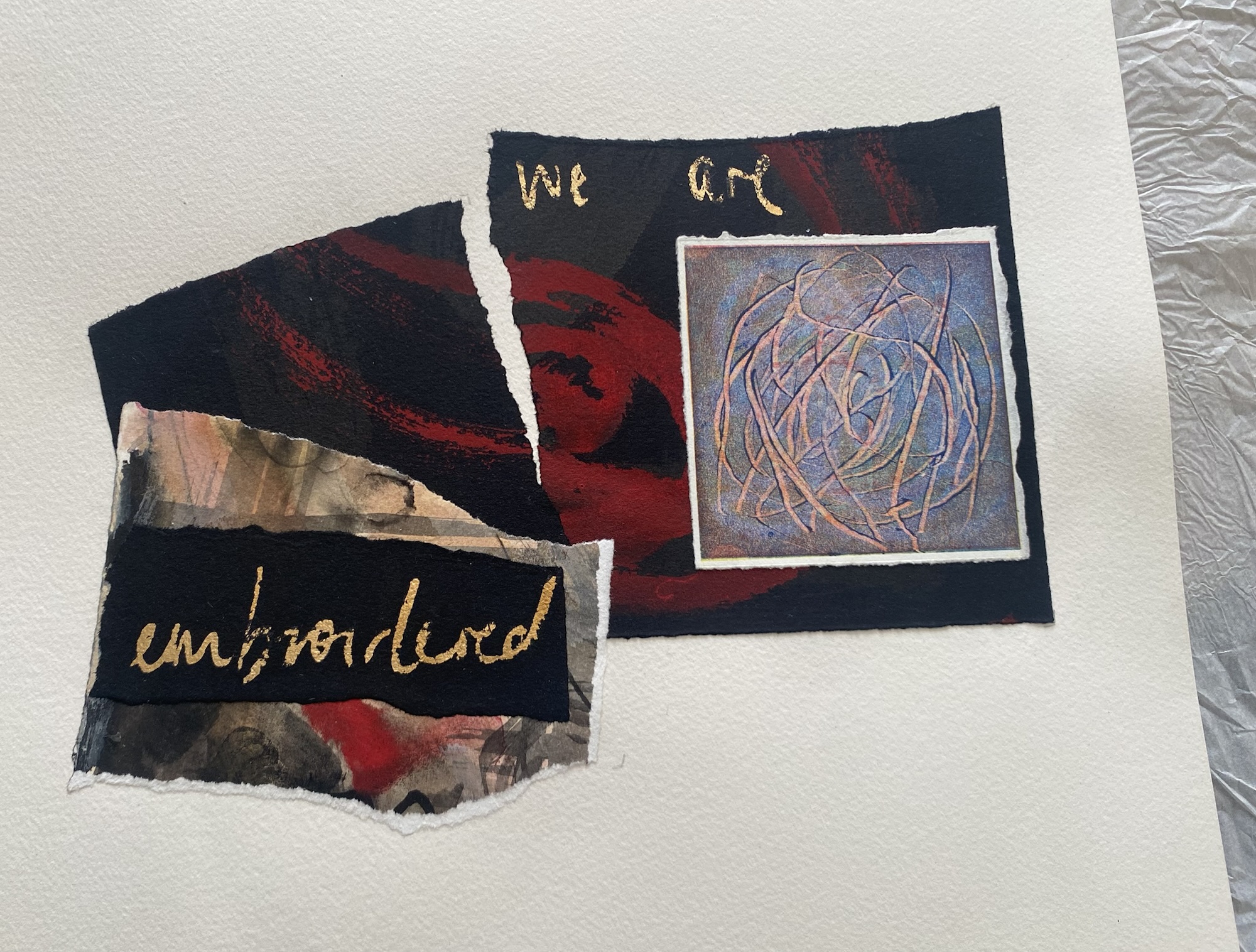

“The thread” is a series of collaged artworks on paper that I made to explore a poem in depth – by taking it apart into fragments and reworking it. The poem is one that I had written myself, about a family story and heirloom, a gift:

The thread

My mother said

Her father said

The thread

Is real gold.

Meaning,

Keep this with care daughter;

Meaning,

This veil

Will sail with you,

Will come to shore

Wherever you may land,

This gift,

This patterned cloth

Of crimson red,

This surface dance

Of gold embroidered thread,

This will keep you with care

Daughter,

This will be with you,

To remind you

For forever

Who we are.

This work has partly come out of weekly creative conversations I have had over the last five years with the artist Jen Herzig Smith. Jen talked about her aspirations – about the work of becoming a good ancestor. And so I came to pay attention to this question of ancestry, one which I had worked hard in my life, I think, to avoid.

I noticed that one aspect of working with the aspiration to become an ancestor is that we will not know now, and may never know, the impact or influence of the work that we do. Another aspect that I quickly noticed is that in order to be an ancestor, one must somehow find reconnection with one’s own ancestors, in the sense of being opened up to being guided by them.

I am fortunate that my aunt has done a huge piece of research work, making a family tree for herself and her siblings. She made it on a pre-printed sheet of paper, a “tree” that records parents, grandparents and so on, and she shared it with us. The first thing I noticed, looking at the paper tree, was that a whole half of the sheet was blank, missing. The pre-printed paper tree reminded me of the cleft oak on the path in this valley, the oak tree that was snapped off in a terrible storm.

The roots of my grandmother’s side of the paper, on the Southampton side, seem to thicken and spread out to the edges of the paper, back as far as the sixth generation from my own. The other half of the tree, the blank side, is my grandfather’s side, the Mauritian Collendavelloos. It is a half of my aunt’s family tree, a quarter of mine. The invisible part of the tree is where my grandfather was rooted. The tree roots can be traced back only as far as four ancestors, arriving on the island of Mauritius around the 1860’s: my grandfather’s four grandparents. Many, perhaps most, of the British colonial records for the island have been lost, more than one person of Mauritian descent has told me this. One person told me that she had heard that they were deliberately destroyed, as an act of aggression.

A brief account of the history is this: after the abolition of slavery, a bargain was struck between the colonial governments and plantation owners to create laws that would make it possible to import hundreds of thousands of bonded labourers. This was in addition to a fortune that was paid in compensation to the businesses for the “loss” of “their” slaves. The previously-enslaved people of African descent left the plantations, and people from the Indian sub-continent were imported as bonded labourers; to balance the books, to be the impossibly cheap work-force that could continue to enrich the plantation owners. The indentured labourers had already been impoverished by the conditions of the British Empire, forced into leaving the places that they came from. They were displaced because of the conditions of exploitation, extractive plundering, famine and coercion. They signed papers and worked for a pittance for a certain number of years. Often, they were treated very badly. These were unfree people therefore; bonded, bound.

It is very difficult, probably impossible, for me to find out what brought my four ancestors to Mauritius from India and Sri Lanka. Some were probably brought as indentured labourers, while it is possible that others came as a result of something that felt like an opportunity, and perhaps what happened was what we call choice, what passes for choice; but for most of the arrivals it wasn’t choice, cogs were turning in a vast legalised machinery of travesty. My ancestors on all sides are implicated in this crime, folded in, one way or another, as are we all. It is as well to be very honest about the ground we are standing on.

I did make another family tree, for the half of my aunt’s tree that is bare. I made it as a gift to my mother. Making the tree, I looked sideways, including as many as I could of the children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren of those four ancestors; all the siblings and spouses that I could find on my aunt’s documents: sisters, brothers, aunts, uncles, nieces, nephews, cousins, husbands, wives, civil partners. As a consequence of the sizes of the families of the Mauritians of those generations, what emerged was a multitude. My grandfather, for example, was one of twelve. I left spaces, and I left the tree open at the twiggy ends, for the ones who have not been born yet, for the ones I had forgotten, or whose names I couldn’t remember. I picked my largest sheet of watercolour paper, but although I had left out all of my own generation and our children, except for a few dozen in my immediate Collen family here in Britain, it was difficult to fit us on the paper. What I had drawn was not a family tree, but a family thicket.

I made our family thicket in colour. Amongst the colours that found their way towards my brushes were crimson and gold leaf. Much later, I realised that I had made it in the colours of a particular fabric, a sari that was a gift to my mother from her father, brought back from the last trip that he made to Mauritius before he died.

This sari, then, became the starting point for my poem, and for this series of work: “the thread”.