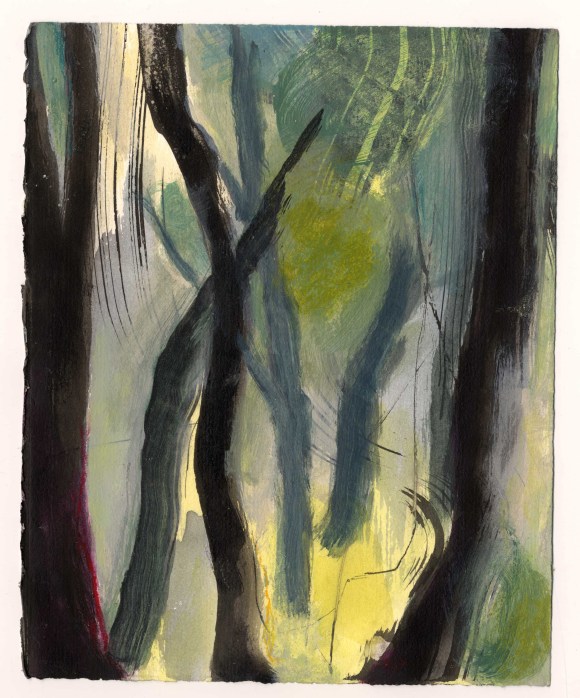

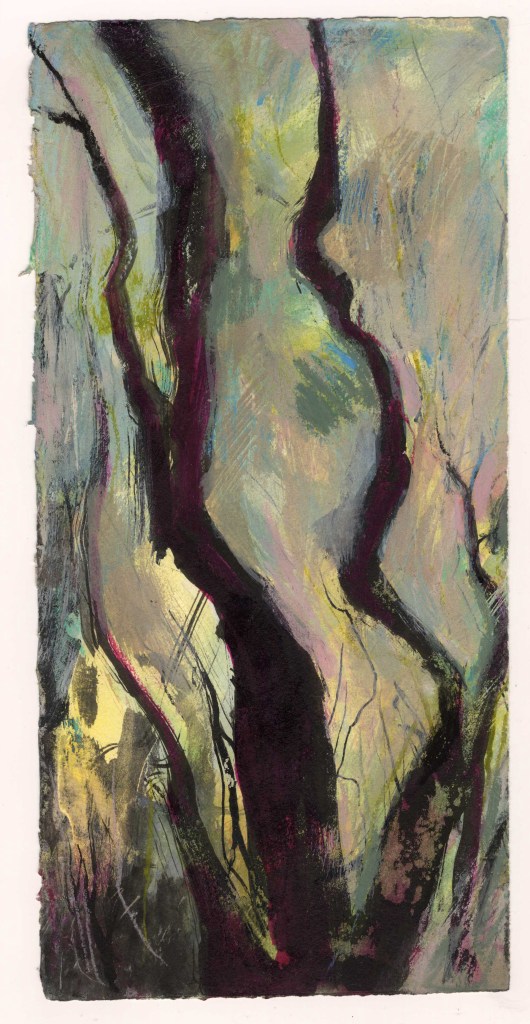

Gwaith mewn paent sy wedi’i ysbrydoli gan gerdded yng Nghwm Gwendraeth.

Paintings that come from time I take walking in the Gwendraeth Valley, especially along the disused mineral railway to Gwendraeth Colliery: Pontyberem Colliery, Pentremawr Colliery, Glynhebog, and Dynant Fawr opencast.

2024

“They heard a fearful roar in the further end of the pit.”

(The London Times, May 1852)

“Apparently conditions at the mine had not been good for some time…

“The site thereafter became known as Y Syrthfa, which means “collapse”,

Though this is not a true explanation of what happened.”

(J. Edmund Healy, Carmarthenshire Historian)

witness

(an extract from my Notes on Care)

(3)

08/08. Attention to the way things are. Which

is not to say the way I want them

to be. But just as they are. With the

pain or discomfort. With the loss.

With the awkwardness ^ the fear…

There is a blackthorn thicket at the top of what my neighbours call Syrthfa field; a field that is not a field, behind our houses. The name Syrthfa has to do with a place of falling, collapse. The piece of land between my home, the river and the village park is overgrown, humped and lumpy, shaped by the land-forming that happened with coal mining. In the village is a stone memorial plaque, remembering a disaster that happened on the 10th of May 1852 in Gwendraeth Colliery, a sudden in-rush of water and mud, when twenty-six men and boys were killed. The Carmarthenshire Historian journal says this:

“It was the worst mining catastrophe ever to occur in the Gwendraeth Valley. The mine was drowned, and it took some weeks to recover the bodies. Apparently conditions at the mine had not been good for some time… The colliery had to be closed, and the site thereafter became known as Y Syrthfa, which means “collapse”, though this is not a true explanation of what happened.”

A London Times newspaper report from 1852 says this:

“At the place over the spot where the water rushed in there have been large sinkings in the surface of the field, which bear out the supposition that there had been an accumulation of water in an old working, which had burst into the pit. A large portion of the field over the pit was sunk from 10 to 12 feet.”

I do not know whether Syrthfa field behind our houses refers to that falling, or to another falling. A neighbour mows a path to the top, but mostly the field is thicket now, a bird-place.

I am ducking through and under this thicket one day, heading for the river bank. I’m following a path that is getting smaller and smaller: it is a path, a badger-way, a rabbit-way, a mouse-way; there is mud on my knees and I have snagged my clothes, there are thorns in my skin, twigs in my hair.

As I head in deeper, I think about these thickets that are growing over the places of tragedy and collapse. I am thinking that if I can say anything about myself, it is that I am widely experienced in stumbling and crawling through the thickets of being human. Also, that although I may at times feel alone in this, the truth is that I am not. Thicket-crawling is something that a lot of us do, one way or another. Perhaps we could be realistic about it, stop spending so much time pretending that we are never in the thickets and learn to acknowledge how often we are down here where we cannot see clear paths. If we acknowledged that, could we finally learn how to slow down, how to do less harm as we crash through? That might be something worth writing about, a worthwhile personal and civilisational aspiration.

I introduce thickets into these notes about care because at some point I find that I am working part-time as a personal assistant and carer. This happened, in the way that our feet carry us on paths. We may choose to call it chance. The work has felt, at times, like a thicket. It has caused me to put myself into difficult situations, ones that I want to avoid, in which I am implicated, incompetent, lacking a clear path. There have been many many times when I have thought “why am I still doing this?” And yet, of all the things that I do and have done, it is one of the least ambiguous, the most clearly valuable, so I have slowly found that it is possible to learn to ask better questions. Many of my learnings from this work are not easy to articulate, they are bodily and emotional intelligences, and they have come hard to me.

I worked with a man who had a terminal illness, a rapidly increasing brain cancer. He was the father of a close friend, a person who I had known from childhood. We agreed that I would work for the family in his last months of life.

My friend leaves him with her father one day, she is desperate to get out and away for the day, desperate for a break. He takes the opportunity to stride across the field behind their house and into the alder woods that line the stream, a walk which he has always done, but is no longer able to do. He was a large man, and he had always been stubborn, perhaps more so than any person I have ever known, and in truth I had always been intimidated by him. Neither I nor his oldest friend, also there that morning, is able to persuade him or to prevent him from setting out. I am only able to follow, with the idea of limiting the damage, bringing him back home.

He crashes into the woods, falls and skids feet first down a steep bank, gets up and wades through a marsh towards the stream, climbing over and under fallen branches. Brambles tangle around him and he stops. He is confused, held. I use this moment to reach him with what authority I can muster, to explain that it isn’t a good thing to go on, that I know the way back but that we need to walk around, he needs to follow me.

We go right around the bank and up a rough path on its long side. We go on our hands and knees for long stretches, because by this time he is not well enough to walk this far. We rest on the ground in the woods, just below the house. I am holding the hand of this proud and independent man, and he has begun to cry. I think he cries because in this moment he has realised that he is not going to get better, that he is going to die very soon. His friend brings tea and we drink it and recover ourselves a little. We get back to the house scratched and muddy and exhausted, crawling across the field on our hands and knees. We get to the house just in time for his grandchildren to arrive and travel the last few yards with us.

It is hard to understand what has happened on this day. For a time, I felt that I failed the family and this man; failed to do what was needed from me. In caring for an unwell person, one may expect censure, by most measures, for allowing a situation to arise which involves crawling through thickets.

What happened though was something I could not prevent. And the things that are given to us to do are small things. The work is to turn our faces to the small things, whether or not we are ready or competent. Anyone can do work like this – but it is muddy, awkward, close to the ground, painful.

What we might notice from this story is that travelling this far into the thickets, putting to one side for a moment the sense of inadequacy and shame, we may start to touch joy. It meets us on the far side of sorrow, we can touch on the authenticity of what we may become, with all the mistakes and the humanness present and available to the eyes, the ears, the heart.